BALANCING PERIOPERATIVE COAGULATION RISKS: A CASE REPORT

Enyinnaya Mike1, Uwanuruochi Kelechukwu1,2

1 Department of Surgery, Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia, Nigeria

2 Department of Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Gregory University Uturu

Abstract

There is need to improve perioperative risks of thrombosis and bleeding. We reported a 63-year old woman who had a cardiac arrest following a clinical impression of massive pulmonary embolism few days after herniorrhaphy. We discuss measures which if followed will reduce perioperative coagulation risks.

Key words: Deep venous thrombosis, anticoagulation, perioperative

Key Message: The measures to minimize perioperative coagulation problems should be appreciated.

Cite: Uwanuruochi K, Mike E. Balancing perioperative coagulation risks: a case report. Yen Med J. 2025 Dec 5;6(1): 15-22

Case report

A 63-year-old female who hails from Akwa Ibom State presented to the Cardiologist in our medical centre ten years ago with history of insomnia, frontal headache, chest pain and uncontrolled home blood pressure measurements (about 150/100 mmHg). She has been living with hypertension and diabetes for ten years, taking the following medication: carvedilol 6.25 mg daily, telmisartan 40 mg daily, amlodipine 5 mg daily, clopidogrel 75 mg daily and metformin 1 g daily.

On clinical evaluation of the patient, her blood pressure was 120/90mmHg, and the pulse yielded a rate of 92 beats/minute, full-volume, irregular, synchronic with peripheral pulses. The arterial wall was thickened. The temperature was 37.0 0C, respiration 30/minute with apex beat at 6th left intercostals space, mid-clavicular. She was moderately obese.

She had a random blood sugar of 276 mg/dl. Electrocardiogram showed a heart rate of 74/minute, with features in keeping with atrial fibrillation and chest radiograph showing cardiomegaly of biventricular configuration, with 0.65 cardiothoracic ratio, unfolded aorta. Two-dimensional echocardiogram study was abnormal with ejection fraction of 38.25%, fractional shortening 18.66, septal wall motion abnormalities, thick calcified anterior mitral valve leaflet, and absent late atrial filling. HDL-Cholesterol 37 mg/dl, LDL-Cholesterol 76 mg/dl and total cholesterol 126mg/dl, and triglycerides 69 mg/dl, HbA1c 5.61%, serum creatinine 0.6 mg/dl, Hb 13.3 g/dl. Abdominal ultrasound showed liver span of 14cm with regular margins and preserved parenchymal echogenicity.

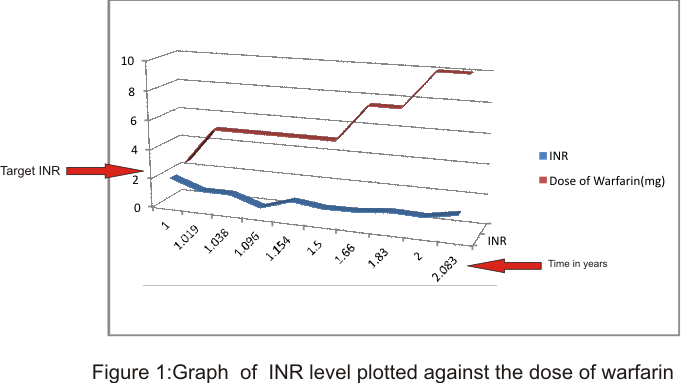

Medications were adjusted over the months. Clopidogrel was withdrawn when she developed dyspepsia. Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was added, with spironolactone 25 mg daily. On commencing dabigatran She developed hematuria with rise in blood pressure (systolic blood pressures of about 150 to 160 mmHg) probably related to stress of the hematuria, , so it was withheld and replaced with warfarin 2.5mg daily, with adjustment according to sequential international normalized ratio (INR) records as depicted in the graph. She was educated on compliance but target INR was not achieved.

Medications were adjusted to the following: carvedilol 12.5 mg twice daily, losartan 50 mg twice daily, digoxin 0.25 mg daily, spironolactone 25 mg daily, and warfarin 10 mg daily. On 14th July 2023, she was referred by the general surgeon for perioperative evaluation prior to inguinal herniorrhaphy. She was advised to stop warfarin three days prior to surgery, to recommence three days post-operation. However, three days after herniorrhaphy she developed breathlessness with mild exertion. She was transferred from the surgery to the medical ward. On entering the ward, and being placed in bed, she was noted to be breathless, sweating, pulseless with cold extremities, warranting an impression of cardiac arrest. An immediate cardiac resuscitation was unsuccessful. An impression of sudden cardiac death from ventricular tachycardia, to rule out acute pulmonary embolism was made but autopsy was not carried out due to psychosocial issues.

Discussion

The inadequacy of perioperative coagulation management has been appreciated by local workers1, and our study attempts to emphasize steps that improve assessment and management of perioperative thrombo-embolism and bleeding risk. A standard practice in many hospitals has been the withholding of warfarin or other anticoagulant for about five days2, but practitioners must understand that this general precaution no longer suffices. The recommendations of the seventh American College of Chest Physicians’ (ACCP) Consensus on antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy3 has been widely accepted, and it emphasized the need for individualized assessment, which avoids overlooking of individual risks. ACCP guidelines also simplifies risk assessment by assigning patients to one of four venous thrombo-embolism (VTE) risk levels-low(0-1 risk factors), moderate(2), high(3-4), highest(5 or more). The risk factors identified include increasing age, prolonged immobility, malignancy, major surgery, multiple trauma, prior VTE, and chronic heart failure. On grounds of age, heart failure and surgery, our patient had a high risk, and as such required treatment with elastic stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression, low-dose unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin. Of note also, in the eight edition, ACCP recommended thrombo-prophylaxis with a low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), low-dose unfractionated heparin (LDUH), or fondaparinux for patients undergoing major general surgery4.

More attention to these guidelines would have improved our patient outcome. Local hospitals must also be encouraged to procure intermittent pneumatic compression and elastic stockings.

The use of risk assessment models must also be emphasized. The CAPRINI model where all possible risk factors are queried to identify the extent of individual risk patient and thrombosis prophylaxis is individualized on the basis of the results of this analysis, is widely accepted and should be adopted in every hospital5. The questionnaire should be readily available and filling it should be a preoperative requirement. Clinicians are well advised to keep a copy of the chart in their phones for ease of reference. CAPRINI risk factors in our patient include age 41-60, BMI above 25, biventricular cardiac failure, major surgery over 45 minutes, giving a total score of 5.

Studies have reported a high risk of DVT with CAPRINI total risk factor score 3-4, for which intermittent pneumatic compression, low dose unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin are recommended6.

Physicians must no longer view formal risk assessment as cumbersome. It is simple with recourse to readily available models. Patients may even prefer to avoid quality-of-life (as opposed to life-saving) procedures if their risk of thrombosis is very high. It may however be observed that CAPRINI does not include atrial fibrillation, a prothrombotic condition in our patient, and that serological test for hereditary thrombophilia are not readily available in local centres. Based on these, local modifications to improve its utility should also be encouraged. It must also be added that multidisciplinary approach, involving anathesiologist, nurses, patient (education) and patient relatives in risk assessment will aid in covering gaps and improve compliance to prevention strategies.

Another model is the Padua Risk Assessment Model for Medical Patients6. It includes active cancer, previous venous thrombo-embolism (with the exclusion of superficial vein thrombosis), reduced mobility and already known thrombo-philic condition (3 points each); recent (≤1 month) trauma or surgery (2 points) and elderly age (≥70 y), heart or respiratory failure, acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, acute infection or rheumatological disorder, obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and ongoing hormonal treatment (all 1 point each). In Padua model, a prediction score of >4 indicates high risk of venous thrombo-embolism; our patient had a score of 5.

Padua model has however been validated mainly for nonsurgical patients, and the power to predict DVT in surgical patients, and need for thrombo-prophylaxis, has been found to be only moderately lower than that of the Caprini score.

Risk factors in our patient include obesity, atrial fibrillation, cardiac failure, surgery and diabetes. The inability to achieve target INR despite moderate dose warfarin, possibly attributable to warfarin resistance, may be noted as an additional risk.

The need to resume warfarin a day after surgery is often overlooked. This is necessary due to the delayed anticoagulant effects8.

The indications for bridging anticoagulation must also be appreciated. Bridging is usually the use of low-molecular-weight heparin to minimize time off anticoagulation and reduce the risk of thrombosis. It can cover the loss of anticoagulation from the long half-life of warfarin and has been recommended where there’s a history of recent VTE (within the past 3 months), presence of mechanical heart valves, or multiple risk factors for thrombo-embolism (like a high CHA2DS2-VASc score in atrial fibrillation9. The CHA2DS2-VASc score assesses the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. It assesses the following risk factors: biventricular heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction (1 point), hypertension (1 point), age ≥75 years (2 points), diabetes mellitus (1 point), stroke, transient ischemic attack, or thrombo-embolism (2 points), vascular disease (1 point), age 65-74 years (1 point) and sex category (female) (1 point). A score of 2 or greater is termed high. Our patient had 4 points, suggesting he would have benefitted from bridging. A meta-analysis suggests that patients with 2005 CAPRINI scores of 7 or above benefit10. However, the bridge trial reports that bridging did not reduce risk of deep vein thrombosis even for patients on warfarin, so this is still an area of controversy11.

In conclusion we recommend assessing patients for risk individually, using a risk assessment model such as CAPRINI, keeping a copy of the model readily available in the ward, theatre or phone, resuming warfarin a day after surgery, procuring intermittent pneumatic compression and elastic stockings and using low-molecular heparin, perioperatively for those with multiple risk factors for thrombo-embolism.

References

- Okorafor UC, Okorafor UC. Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment and Prophylaxis Administration among Admitted Patients in Lagos, Nigeria: A Quality Improvement Project. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2025 May;35(3):179-184. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v35i3.5. PMID: 40717716; PMCID: PMC12287704.

- Tran HA, Chunilal SD, Harper PL, Tran H, Wood EM, Gallus AS; Australasian Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ASTH). An update of consensus guidelines for warfarin reversal. Med J Aust. 2013 Mar 4;198(4):198-9. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10614. PMID: 23451962.

- Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004;126(suppl 3):338S-400S.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, Colwell CW. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008 Jun;133(6 Suppl):381S-453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. PMID: 18574271.

- Caprini JA. Thrombosis risk assessment as a guide to quality patient care. Dis Mon. 2005 Feb-Mar;51(2-3):70-8. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2005.02.003. PMID: 15900257.

- Henke PK, Kahn SR, Pannucci CJ, Secemksy EA, Evans NS, Khorana AA, Creager MA, Pradhan AD; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee. Call to Action to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Patients: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Jun 16;141(24):e914-e931.

- Anand V, Ramakrishnan D, Jha RK, Shankaran R, Mishra A, Dwivedi SK. Comparison of Caprini’s and Padua’s risk assessment scores in the prediction of deep vein thrombosis in surgical patients at a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Surgery. 2023 Feb;85(Suppl 1):141-6.

- Jaffer AK, Brotman DJ, Chukwumerije N. When patients on warfarin need surgery. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, Becker RC, Caprini JA, Dunn AS, Garcia DA, Jacobson A, Jaffer AK, Kong DF, Schulman S, Turpie AG, Hasselblad V, Ortel TL; BRIDGE Investigators. Perioperative Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 27;373(9):823-33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501035. Epub 2015 Jun 22. PMID: 26095867; PMCID: PMC4931686.

- Pannucci CJ, Swistun L, MacDonald JK, Henke PK, Brooke BS. Individualized venous thromboembolism risk stratification using the 2005 Caprini score to identify the benefits and harms of chemoprophylaxis in surgical patients: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2017;265:1094–1103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002126

- Berry J, Patell R, Zwicker JI. The bridging conundrum: perioperative management of direct oral anticoagulants for venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2023 Apr;21(4):780-786. doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2022.12.024. Epub 2023 Jan 2. PMID: 36709100; PMCID: PMC11000626.