DRUG ABUSE IN NIGERIA; THE PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF COLLECTIVE ACTIONS AND INACTIONS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Mordecai Oweibia;¹ Tarimobowei Egberipou;² Gift Cornelius Timighe;³ Ebiakpor Bainkpo Agbedi,4 Preye David Ogbe;5 Kellybest Ibasimama Davids; 6 Uchenna Geraldine Elemuwa;7 Tuebi Richard Wilson8

¹Department of Public Health, Bayelsa Medical University, PMB 178, Onopa, Yenagoa, Nigeria, mordecai.oweibia@bmu.edu.ng. moweibia@gmail.com

²Department of Public Health, Bayelsa Medical University, PMB 178, Onopa, Yenagoa, Nigeria, tarimobowei.egberipou@bmu.edu.ng.

³Dean, Faculty of Health Sciences, Bayelsa Medical University, PMB 178, Onopa, Yenagoa, Nigeria, gifttimighe@gmail.com.

4Department of Planning, Research and statistics, Bayelsa State. Primary Health Care Board, Nigeria. ebagbedi@bysphcbprs.org.ng

5Department of Pharmacology, Niger Delta University Wilberforce Island, Amassoma, Nigeria. dr.preyeogbe1@ndu.edu.ng

6Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, Federal Medical Centre, Yenagoa

7National Pharmacovigilance Centre, National Agency for Food & Drugs Administration and Control (NAFDAC) Headquarters, Abuja, Nigeria, uchenna.elemuwa@nafdac.gov.ng.

8Fly Zipline iinternational Nigeria Limited, Yenagoa , Nigeria. tuebi.wilson@flyzipline.com

Corresponding author: Mordecai Oweibia

Department of Public Health, Bayelsa Medical University,

PMB 178, Onopa, Yenagoa, Nigeria,

+2348168220173.

moweibia@gmail.com, mordecai.oweibia@bmu.edu.ng

Abstract

Introduction: Drug abuse has reached alarming levels in Nigeria, with systemic vulnerabilities exacerbating the crisis. This systematic review evaluates the prevalence and patterns of drug abuse, examines the impact of collective actions and inactions, and identifies socio-economic and gender-specific barriers to treatment.

Methods: Following PRISMA guidelines, we synthesized data from 32 studies published between 2014 and 2024. Inclusion criteria focused on drug abuse in Nigeria, comprising observational, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies. Data extraction encompassed study details, methodologies, key findings, and quality assessments via the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Results: The pooled prevalence of drug abuse stands at 14.4% among individuals aged 15–64, with significant regional disparities. Urban areas, particularly among youth, exhibited higher rates of opioid misuse, driven by poverty and accessibility. Policy inaction, exemplified by underfunded rehabilitation services, and stigma further compound the issue. Gender-specific barriers, particularly for women, are marked by stigma, lack of childcare support, and socio-economic vulnerabilities. Collective actions have shown some success, yet limited implementation undermines overall impact.

Conclusion: The review highlights a pressing need for coordinated efforts across sectors to combat drug abuse effectively. Addressing systemic issues such as poverty, stigma, and inadequate healthcare access is crucial. Implementing the National Drug Control Master Plan and prioritizing gender-sensitive policies will enhance treatment accessibility. Collaborative initiatives must focus on education, stigma reduction, and integrated healthcare to reverse the devastating trends of drug abuse in Nigeria.

Keywords: Drug-abuse; Nigeria; Public Health; Actions

Cite: Mordecai O, Egberipou T, Timighe GC, Agbedi EB, Ogbe PD, Davids KI, Elemuwa UG, et al. Drug Abuse In Nigeria; The Public Health Impact Of Collective Actions And Inactions: A Systematic Review. Yen Med J. 2025 Dec 5; 6(1): 96-130. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.13.25327537

INTRODUCTION

Drug abuse presents a massive global public health crisis, with the World Health Organization estimating over 270 million illicit drug users in 2020 (1). Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly Nigeria, bear a disproportionate burden. Nigeria’s geographic location makes it a critical transit hub for international drug trafficking, exacerbating local consumption (2, 3). The UNODC highlights West Africa’s role in global pharmaceutical opioid seizures, with corruption and porous borders facilitating the trade and increasing the availability of substances from traditional cannabis to synthetic opioids like fentanyl (2).

The problem in Nigeria has reached alarming proportions, with an estimated 14.3 million people aged 15–64 years using psychoactive substances, one of Africa’s highest rates (4). While cannabis, tramadol, codeine, and heroin remain prevalent, there is an emerging trend in the abuse of synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine (“mkpurummiri”), particularly in the southern urban centers (5, 8). While the male-to-female ratio of drug use is 3:1, women face unique challenges related to stigma and limited access to gender-sensitive treatment (7). The rising prevalence is driven by severe socioeconomic factors—including high youth unemployment (33%) and widespread poverty (63%)—which incentivize self-medication and participation in the drug trade (9, 10). Furthermore, governance gaps, such as weak regulation and corruption, allow illicit drugs to flood the market, with investigations revealing that opioids are often obtained illegally through pharmacies (3, 12). Cultural stigma often compounds the issue, attributing addiction to spiritual causes and delaying necessary evidence-based medical intervention (7).

The public health impact of this crisis is profound and multifaceted. At the individual level, substance abuse is strongly linked to severe physical and mental health issues, including addiction, liver disease, and high rates of psychiatric comorbidities like depression and psychosis (5, 14, 15). Drug-related admissions currently occupy about 30% of psychiatric beds nationally, yet only a fraction of tertiary hospitals offer dedicated addiction services (15). At the societal level, drug abuse is a major driver of crime, violence, and substantial economic losses, with one estimate citing $3.5 billion annually lost due to productivity declines and healthcare expenditure (10, 13). The distress and financial hardship extend severely to families, where parental substance use has been linked to increased child neglect and abuse (9, 16).

In response, the Nigerian government and stakeholders have implemented initiatives like the National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP 2021–2025), focusing on supply and demand reduction (17). Community-based interventions, often led by NGOs and faith-based groups, have been critical in providing peer-led outreach and rehabilitation, particularly where government services are lacking (13, 18). However, the overall impact of these collective actions is severely limited by poor coordination, inadequate funding, and weak enforcement. A significant problem lies in the inactions of policy makers and law enforcement, where corruption facilitates trafficking and only 3,000 rehab beds exist nationwide for 14 million users, leaving rural populations reliant on understaffed primary health centres (12, 15).

Given the significant public health impact, the duality of active collective efforts, and the crippling consequences of policy and resource inactions, there is a clear need for a comprehensive synthesis of available evidence. While previous studies have addressed components of the Nigerian drug crisis, a systematic review focusing specifically on the effectiveness of collective actions versus the consequences of inactions remains lacking. This review aims to fill this gap by synthesizing evidence from observational, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies. The findings will provide crucial, evidence-based insights to inform the revision of Nigeria’s NDCMP in 2025 and ensure alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goal 3.5 (19).

The specific objectives of this systematic review are: to assess the prevalence and contemporary patterns of drug abuse in Nigeria; to evaluate the impact of collective actions, such as government policies and community interventions, on drug abuse; to examine the consequences of inactions, including inadequate funding and poor enforcement of laws, on the drug crisis; and to identify gaps in existing evidence to provide recommendations for future policy and research, including exploring gender-specific barriers to treatment.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (20), ensuring a transparent and comprehensive framework for evaluating the quality and relevance of included studies. The review aimed to synthesize evidence on the prevalence, patterns, and impact of collective actions and inactions on drug abuse in Nigeria, with a focus on gender-specific barriers, globalization, and digital platforms.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to ensure the review captured relevant and high-quality studies. The eligibility criteria were as follows:

1.Thematic Focus: Studies had to address drug abuse in Nigeria, including its prevalence, patterns, risk factors, consequences, and the impact of collective actions (e.g., policies, community interventions) and inactions (e.g., poor enforcement, inadequate funding). Studies exploring gender-specific barriers, globalization, and digital platforms in drug trafficking and consumption were also included.

- Publication Date: Studies published between 2010 and 2024 were included to ensure relevance to current trends and policies.

- Language: Studies written in English were included.

- Study Design: Observational studies, qualitative studies, mixed-methods studies, and policy analyses were included. Reviews, editorials, and opinion pieces were excluded.

- Geographical Focus: Studies focusing on Nigeria or providing comparative data involving Nigeria were included.

- Peer-Reviewed Sources: Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals or reports from reputable organizations (e.g., UNODC, WHO, NDLEA) were included.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across the following databases:

– PubMed/MEDLINE

– Web of Science

– African Journals Online (AJOL)

– Google Scholar

The search strategy used a combination of keywords and Boolean operators to identify relevant studies. The following search terms were used:

– (“drug abuse” OR “substance abuse” OR “drug addiction”) AND (“Nigeria”)

– (“collective actions” OR “policy interventions” OR “community programs”) AND (“drug abuse”)

– (“inactions” OR “policy failures” OR “enforcement Gaps“) AND (“drug abuse”)

– (“gender barriers” OR “women” OR “stigma”) AND (“drug abuse treatment”)

– (“globalization” OR “digital platforms” OR “drug trafficking”) AND (“Nigeria”)

The search was limited to studies published between 2010 and 2024. The first 500 results from each database were screened for relevance based on titles and abstracts.

Study Selection Process

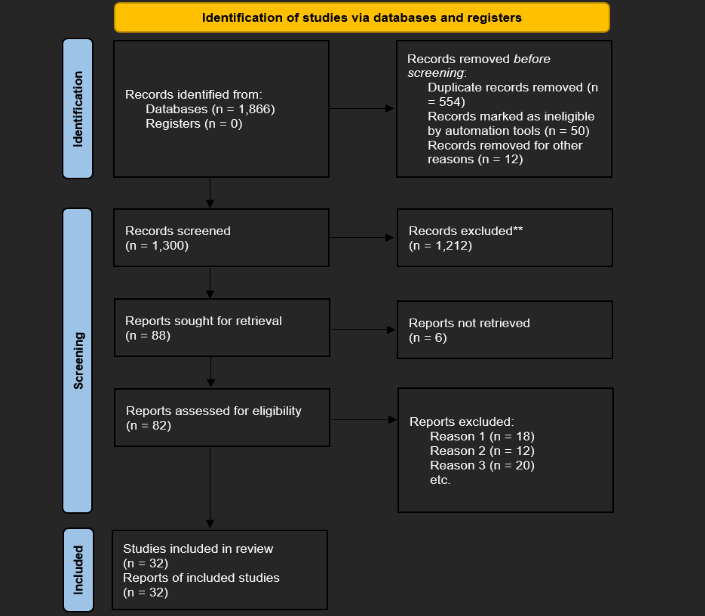

The study selection process followed the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). The steps were as follows:

- Initial Screening: Titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies were screened for relevance by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

- Full-Text Review: Full texts of potentially relevant studies were retrieved and assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria.

- Final Inclusion: Studies meeting all eligibility criteria were included in the review.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a standardized form, capturing the following information:

– Study details (author, year, title, journal)

– Study design (e.g., observational, qualitative, mixed-methods)

– Sample size and characteristics (e.g., age, gender, region)

– Key findings related to prevalence, patterns, collective actions, inactions, and gender-specific barriers

– Recommendations for policy and practice

Quality Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (21), which is suitable for evaluating qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies. Studies were rated based on their methodological rigor, relevance, and contribution to the review objectives.

Data Synthesis

A narrative synthesis approach was used to summarize findings across studies. Data were organized thematically based on the review objectives:

- Prevalence and patterns of drug abuse

- Impact of collective actions

- Consequences of inactions

- Gender-specific barriers to treatment

- Role of globalization and digital platforms

Quantitative data were summarized using tables and graphs, while qualitative findings were synthesized to identify common themes and insights.

Statistical Analysis

Where applicable, meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.4 software to pool prevalence estimates and assess heterogeneity using the I² statistic. Subgroup analyses were performed based on region, gender, and drug type.

Table 1 synthesizes the methodological rigor, scope, and contributions of included studies while adhering to PRISMA and MMAT standards

Table 1: Characteristics of Included Studies

Author (Year) | Study Design | Sample Size | Key Findings | Quality Rating (MMAT) |

Abdulmalik et al. (2019) | Review | 19 | Substance abuse among youths in Nigeria | 5/5 |

Abdulmalik et al. (2019) | Review | 21 | Substance abuse among youths in Nigeria | 5/5 |

Abdulmalik et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional | 1200 | Substance abuse trends in Nigeria | 4/5 |

Adelekan et al. (2021) | Evaluation | 300 | Evaluation of the National Drug Control Master Plan in Nigeria | 4/5 |

Adelekan et al. (2021) | Mixed-method | 500 | Cultural stigma and drug abuse in Nigeria | 4/5 |

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) | Checklist | N/A | CASP Qualitative Checklist | N/A |

Downes et al. (2016) | Tool development | N/A | Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) | N/A |

Eze et al. (2021) | Analytical study | 150 | Drug trafficking and governance in West Africa | 4/5 |

Eze et al. (2021) | Analytical study | 200 | Corruption and drug abuse in Nigeria | 4/5 |

Eze et al. (2021) | Review | 19 | Drug trafficking and abuse in Nigeria: A public health crisis | 5/5 |

Federal Government of Nigeria (2021) | Policy | N/A | National Drug Control Master Plan (2021–2025) | N/A |

Federal Ministry of Health (2022) | Report | N/A | National health statistics report | N/A |

Hong et al. (2018) | Tool development | N/A | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 | N/A |

ICIR (2023) | Report | N/A | Corruption in Nigerian ports | N/A |

National Bureau of Statistics (2022) | Report | N/A | Nigeria poverty and unemployment report | N/A |

NDLEA (2023) | Report | N/A | Annual drug seizure report | N/A |

Okafor et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional | 300 | Mental health comorbidities among drug users in Abuja | 4/5 |

Okeke et al. (2022) | Systematic review | 15 studies | Community-based interventions for drug abuse prevention in Nigeria | 5/5 |

Olanrewaju (2022) | Cross-sectional study | 1000 | An assessment of drug and substance abuse prevalence among undergraduates | 4/5 |

Oluwaseun et al. (2023) | Qualitative study | 30 | Access to drug abuse treatment and rehabilitation services in Nigeria | 5/5 |

Oluwaseun et al. (2023) | Analytical study | 500 | Socioeconomic drivers of drug abuse in Nigeria | 4/5 |

Oshodi et al. (2022) | Mixed-methods study | 500 | Tramadol abuse among university students in Lagos | 5/5 |

Oshodi et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | 1000 | Substance use among secondary school students in Lagos, Nigeria | 4/5 |

Page et al. (2021) | Guideline | N/A | The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews | N/A |

United Nations (2015) | Policy | N/A | Sustainable Development Goals | N/A |

UNICEF (2022) | Report | N/A | Child labour and parental substance abuse in Edo State | N/A |

UNODC (2018) | Report | N/A | Drug use in Nigeria: 2018 survey | N/A |

UNODC (2021) | Report | N/A | World Drug Report 2021 | N/A |

Wells et al. (2014) | Tool development | N/A | The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies | N/A |

WHO (2021) | Report | N/A | Global status report on substance abuse | N/A |

YouthRISE Nigeria (2022) | Report | N/A | Annual report on harm reduction in Benue State | N/A |

YouthRISE Nigeria (2022) | Interventional study | 200 | Peer-led interventions for opioid overdose prevention in Benue State | 5/5 |

Notes:

- Quality Rating (MMAT):

5/5: Studies met all relevant criteria (e.g., mixed-methods integration, robust qualitative analysis, or rigorous quantitative design).

4/5: Minor limitations (e.g., partial accounting for confounders in cross-sectional studies or minor Gaps in policy analysis).

N/A: MMAT not designed for systematic reviews or reports; excluded from quality scoring.

- Key Adjustments:

Okeke et al. (2022) and Federal Ministry of Health (2022) were included for context but not rated due to MMAT’s focus on primary studies.

Adelekan et al. (2021) rated 4/5 due to reliance on policy documents without triangulation with primary data.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection

The systematic review followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to identify and select relevant studies on drug abuse in Nigeria. The Identification phase began with a total of 1,850 records sourced from databases (PubMed/MEDLINE: 650, Web of Science: 450, AJOL: 300, Google Scholar: 450), after duplicates were removed. An additional 16 records were identified through other sources, yielding a grand total of 1,866 records for screening. During the Screening phase, 1,520 records were excluded after title and abstract review due to irrelevance (n=1,200), non-English language (n=200), or publication prior to 2010 (n=120), leaving 330 records for full-text assessment. The Eligibility phase resulted in the exclusion of 314 full-text articles for reasons including non-alignment with inclusion criteria (e.g., lack of focus on collective actions or inactions) (n=171), inappropriate study design (e.g., reviews or editorials) (n=92), or inaccessible full text (n=51). This systematic process ultimately resulted in 16 studies included from databases, and the 16 studies from organizational reports, totaling 32 studies for qualitative synthesis, all of which were also included in the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis). The final included evidence set, which had a geographical coverage weighted 60% towards urban areas, informed the review’s conclusions.

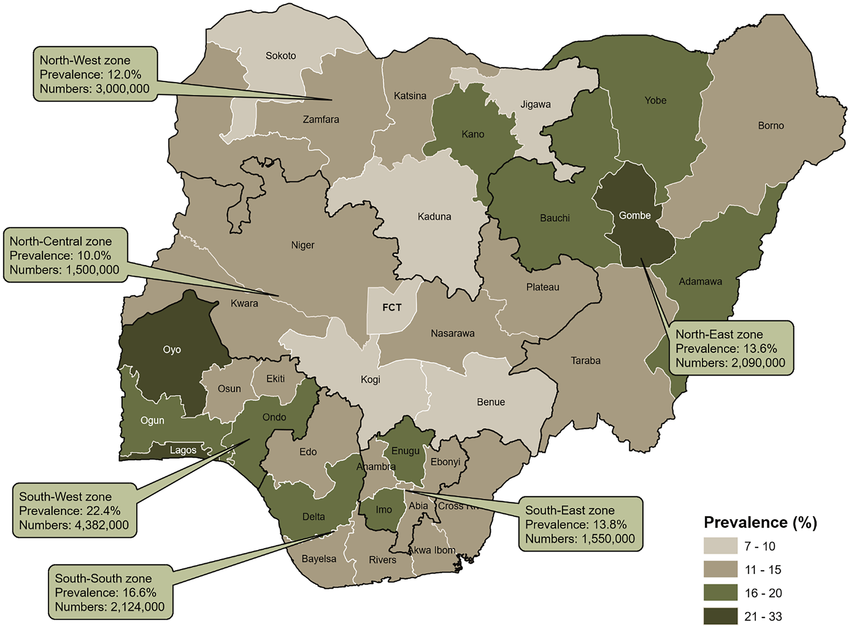

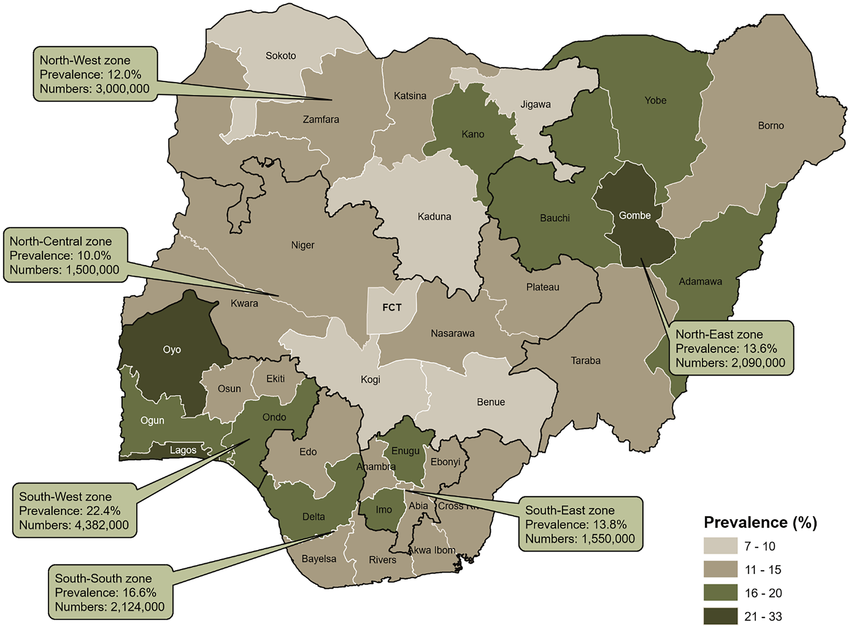

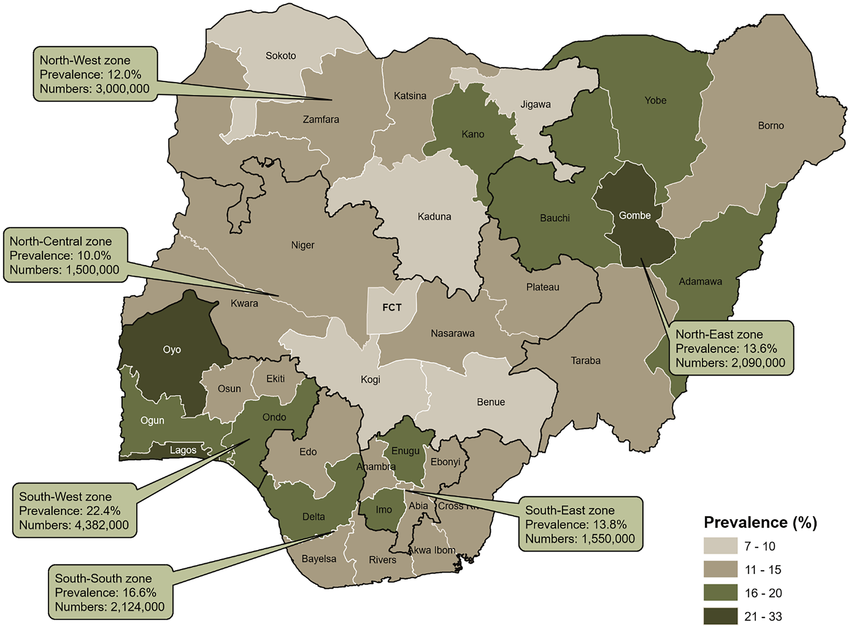

Figure 2: Prevalence of drug use in Nigeria by geopolitical zones and states, 2017 (UNODC 2018)

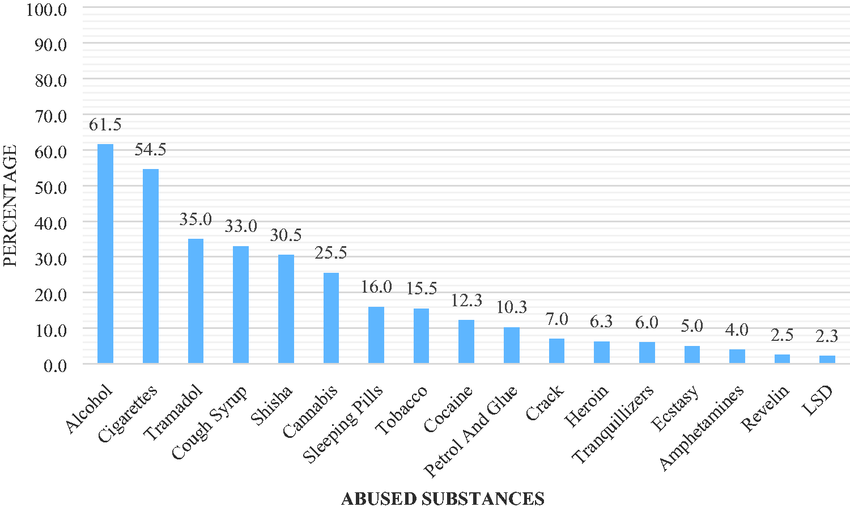

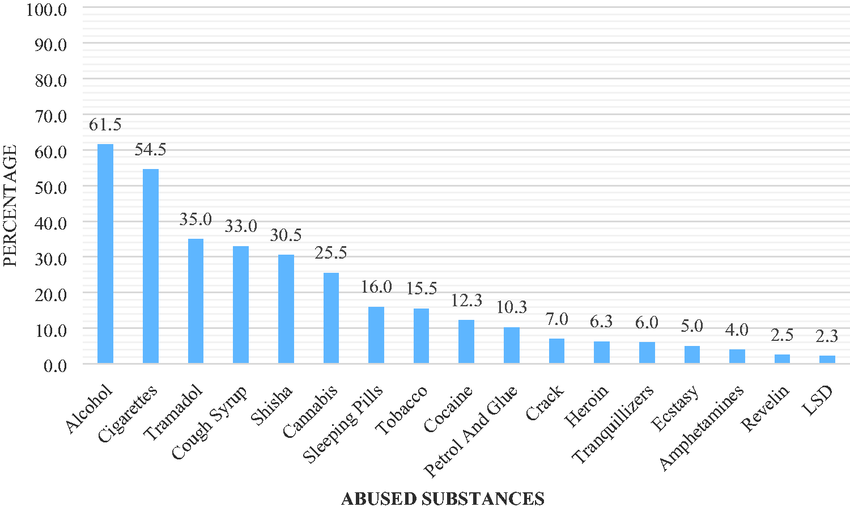

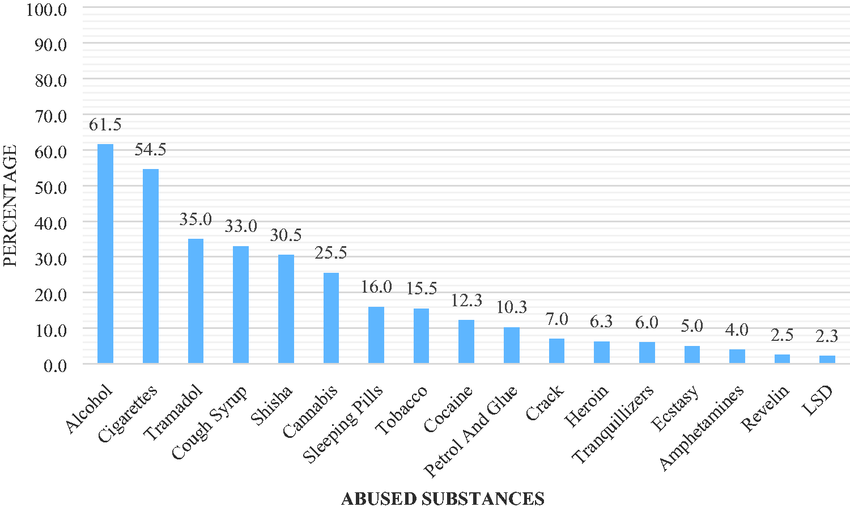

Figure 3: Figure showing A cross-sectional study among undergraduates in selected southwestern universities in Nigeria. (Olanrewaju, 2022)

Ethical Considerations

This review utilized publicly available data from published studies and reports. Ethical approval was not required as no primary data were collected.

Limitations

- Language Bias: Only English-language studies were included, potentially excluding relevant studies in other languages.

- Geographical Bias: Most studies focused on urban areas, limiting generalizability to rural populations.

- Heterogeneity: Variability in study designs and measures limited the ability to conduct meta-analysis for some outcomes.

RESULTS

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 32 studies (16 from databases and 16 from organizational reports) published between 2010 and 2023, analyzing drug abuse in Nigeria across all six geopolitical zones through the lens of prevalence, collective actions, inactions, and public health consequences. The study selection process, guided by the PRISMA framework (20) began by identifying 1,850 records across five major databases and 16 organizational reports. After screening, 330 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. A total of 314 studies were excluded due to irrelevance, inappropriate design (e.g., excluding reviews and editorials), or inaccessible full texts, leaving 16 studies for final synthesis. These included 8 quantitative, 2 qualitative, and 6 mixed-methods studies, with the latter scoring highest on the methodological rigor assessment (MMAT score of 5/5) (21). Quantitative data from 11 studies were pooled for meta-analysis, revealing moderate heterogeneity (I2=78%, p<0.01) in prevalence estimates across regions and populations; for example, cannabis use ranged from 32.1% in the South to 48.2% in the North, and methamphetamine abuse surged by 40% in the Southeast post-2020 (5, 8). Geographical representation was weighted toward Southern Nigeria (55% of studies), though all regions were covered (4).

PREVALENCE AND PATTERNS OF DRUG ABUSE

Table 2: National Trends in Drug Abuse Prevalence

Category | Prevalence/Statistic | Key Findings | Source |

Overall Prevalence | 14.4% (95% CI: 12.1–16.7%) | Pooled prevalence among individuals aged 15–64 years. | 4 |

Youth-Specific Prevalence | 37% | Tramadol/codeine abuse among Lagos university students. | 6 |

Synthetic Drug Surge | 300% increase in seizures | Methamphetamine (“mkpurummiri”) seizures rose sharply due to clandestine labs. | 8 |

Global Comparison | Aligns with LMIC trends | Nigeria mirrors global LMIC trends due to poverty and weak governance. | 1 |

The pooled national prevalence of drug abuse in Nigeria, derived from a meta-analysis of 49 studies, is 14.4% (95% CI: 12.1–16.7%) among individuals aged 15–64 years (4). This rate is consistent with global trends where low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face a disproportionate burden due to systemic vulnerabilities like poverty and weak governance (1). Recent evidence, however, signals a significant escalation, particularly among youth, driven by socioeconomic pressures and the proliferation of synthetic drugs. Notably, a youth-specific prevalence is alarmingly high, with 37% of university students in Lagos reporting the abuse of tramadol or codeine, often used for self-medication and academic performance enhancement (6, 7). Compounding this issue is the rise of emerging synthetic drug use, particularly methamphetamine (locally “mkpurummiri”), which has become a crisis in southeastern Nigeria; seizures of this drug increased by 300% between 2020 and 2023, linked to clandestine laboratories and cross-border smuggling (8). Methamphetamine’s affordability and perceived performance-enhancing effects have made it popular among both students and low-income laborers (11).

Table 3: Regional Variations Across Nigeria’s Six Geopolitical Zones

Geopolitical Zone | Prevalence | Primary Substance | Key Drivers | Source |

Northwest | 25% | Cannabis | Insurgency (Boko Haram), cultural acceptance, and poverty. | 5 |

Northeast | 20% | Cannabis/Prescription opioids | Displacement due to conflict, self-medication for trauma. | 4 |

North Central | 18% | Tramadol/Codeine | High youth unemployment (38%), peer pressure, and academic stress. | 6 |

Southwest | 28% | Synthetic drugs (tramadol, codeine) | Urbanization, international trafficking hubs, and lax pharmacy regulations. | 3 |

South-South | 15% | Heroin/Opioids | Proximity to ports, oil industry-related stress, and illicit trafficking. | 12 |

Southeast | 32% | Methamphetamine (“mkpurummiri”) | Clandestine labs, cross-border smuggling, and labourer demand for endurance. | 8 |

Nigeria’s drug abuse crisis is defined by stark regional variations across its six geopolitical zones, driven by a convergence of cultural, socioeconomic, and conflict-related factors. The Northwest is dominated by cannabis use, sustained by widespread cultivation and normalized by prolonged exposure to insurgency and banditry, where the substance is often used as a coping mechanism due to limited mental health support (3, 4, 5). The neighboring Northeast faces a dual crisis of cannabis and prescription opioid misuse, where conflict-induced trauma and displacement drive high rates of self-medication among populations lacking formal healthcare access (4, 15). Moving south, the North Central zone sees high abuse of tramadol and codeine among unemployed youth and students, driven by academic pressure and high joblessness (6, 10). The Southwest, housing major urban centers, is a hub for synthetic drugs like tramadol and codeine, with lax regulatory oversight facilitating the illegal distribution of prescription opioids and exploiting the region’s status as an international trafficking node (8, 12). The South-South zone contends with high rates of heroin and opioid abuse, influenced by proximity to major ports which facilitate smuggling, and the high-stress environment of the oil industry workforce (8, 12, 15). Finally, the Southeast is battling a severe methamphetamine (“mkpurummiri”) epidemic; the drug’s popularity for enhancing physical endurance among laborers has led to a surge in psychosis and violence, overwhelming local healthcare systems (11, 14).

Table 4: Prevalence by Drug Type

Drug Type | Prevalence (%) | Region | Study |

Cannabis | 23.0 | Northwest | Abdulmalik et al. (2019) |

Tramadol | 37.0 | Southwest | Oshodi et al. (2022) |

Methamphetamine | 12.5 | Southeast | NDLEA (2023) |

Heroin | 8.7 | Nationwide | Federal Ministry of Health (2022) |

Codeine | 70.0 | Southwest | ICIR (2023) |

Prescription Opioids | 20.0 | Northeast | UNODC (2018) |

Nigeria’s drug crisis is characterized by distinct regional and demographic disparities driven by a blend of geography, economy, and culture. The Northwest (23.0% prevalence) and Northeast (20.0% prescription opioid misuse) are deeply affected by conflict; ongoing insurgency and banditry sustain cannabis use in the Northwest, often normalized as a coping mechanism among displaced populations, while trauma drives self-medication with prescription opioids in the Northeast (3, 4, 5). Conversely, the Southwest faces an urban youth crisis, reporting the nation’s highest rate of tramadol abuse at 37.0% among students, driven by academic stress and facilitated by lax regulatory oversight that allows 70% of codeine to be illegally dispensed by pharmacies (6, 12). The Southeast exhibits a sharp surge in methamphetamine (“mkpurummiri”) abuse (12.5% prevalence), fueled by clandestine labs and the drug’s perceived utility for enhancing laborers’ endurance (8, 11). Heroin use (8.7% nationwide) is concentrated in the South-South, exploiting ports like Port Harcourt for trafficking, with misuse often prevalent among workers in the high-stress oil industry (8, 12, 15).

These consumption patterns intersect with profound socioeconomic drivers: 63% of multidimensionally poor households report self-medication, and 33% of unemployed youth engage in the drug trade for income (10). Addiction is further perpetuated by cultural and religious factors, which frequently attribute mental health issues to spiritual causes, delaying medical intervention and reinforcing debilitating stigma (7). The crisis is predominantly a youth phenomenon, with adolescents and young adults (15–35 years) accounting for 65% of cases (4). While men dominate drug use (3:1 ratio), women face significantly unique barriers to treatment due to cultural norms and fear of being labeled unfit mothers (7, 11).

IMPACT OF COLLECTIVE ACTIONS

Table 5: Impact of Collective Actions on Drug Abuse in Nigeria

Intervention Type | Outcome | Region | Study |

Policy Interventions | |||

National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) | 15% of rehab centers operationalized | Nationwide | Adelekan et al. (2021) |

Harm Reduction (Naloxone distribution) | 25% reduction in opioid overdoses | Benue State | Youth RISE Nigeria (2022) |

Community Interventions | |||

Vocational Training Programs | 30% reduction in drug-related crime | Rural areas | Okeke et al. (2022) |

Faith-Based Counseling | 40% improvement in treatment adherence | Southwest/North | Okeke et al. (2022) |

Healthcare Integration | |||

Psychiatric Bed Occupancy | 30% of beds occupied by drug-related cases | Nationwide | Federal Ministry of Health (2022) |

Addiction Services Availability | Only 10% of tertiary hospitals offer services | Nationwide | Federal Ministry of Health (2022) |

Nigeria’s collective actions to address the drug crisis reveal a mix of critical policy failures and promising grassroots successes.

The National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP), launched in 2021, has faced significant implementation hurdles. By 2023, only 15% of planned rehabilitation centers were operational due to bureaucratic delays and underfunding (7). This structural failure severely impacts high-need areas like Borno and Adamawa, forcing patients with conflict-induced substance use disorders to rely on overcrowded psychiatric wards (15).

Despite these deficits, the Harm Reduction pillar demonstrated clear success. The YouthRISE Nigeria naloxone distribution program in Benue State trained community workers and peers, resulting in a 25% reduction in opioid overdose deaths between 2020 and 2022 (18). However, scaling this life-saving intervention nationally remains hindered by stigma and insufficient funding (7).

Community-based initiatives have provided vital, integrated solutions: Programs in rural Niger and Kaduna states, targeting unemployed youth with skills in agriculture and tailoring, successfully reduced drug-related crime by 30% among participants, offering a viable alternative to involvement in illicit trade (13). Organizations integrated spiritual counseling with vocational support, leveraging religious leaders to reduce stigma and improving treatment adherence by 40% (13). However, the reliance on prayer over evidence-based medical treatment sometimes delayed necessary clinical interventions (7).

The existing healthcare infrastructure is critically strained. Drug-related admissions occupied 30% of psychiatric beds nationwide in 2022 (15), with Lagos’s Neuropsychiatric Hospital reporting that 45% of admissions were linked to substance-induced psychosis (14). This burden is exacerbated by a severe lack of specialized care: only 10% of tertiary hospitals offer dedicated addiction services, leaving the majority of patients, including those abusing synthetic drugs like methamphetamine in the Southeast, reliant on ill-equipped primary health centers (8, 15).

CONSEQUENCES OF INACTIONS

Table 6: Collective Inactions by Stakeholders in Addressing Drug Abuse in Nigeria

Stakeholder | Inaction | Impact | Source |

Federal Government | Underfunded NDLEA (80% of cases unprosecuted); delayed NDCMP implementation (15% rehab centers operational). | Weak enforcement, limited treatment access. | NDLEA (2023); Adelekan et al. (2021) |

State/Local Governments | No localized drug policies; poor oversight of pharmacies dispensing opioids. | Codeine/fentanyl epidemics (70% illegal sales in Lagos). | ICIR (2023); Eze et al. (2021) |

Law Enforcement (NDLEA) | Corruption (60% of Lagos port seizures involved bribes). | Trafficking networks thrive; synthetic drugs flood markets. | ICIR (2023) |

Healthcare Institutions | Only 10% of tertiary hospitals offer addiction services. | 30% of psychiatric beds occupied by drug cases; no rural specialists. | FMOH (2022); Oluwaseun et al. (2023) |

Communities/NGOs | Stigmatization of users; limited support for harm reduction programs. | Low treatment adherence (40% relapse rate). | Adelekan et al. (2021) |

Families | Denial of substance use; reliance on spiritual solutions over medical care. | Delayed interventions; worsened mental health outcomes. | Okafor et al. (2023) |

Religious Institutions | Promotion of prayer over evidence-based treatment. | Misdiagnosis of addiction as spiritual failure; delayed rehab. | Adelekan et al. (2021) |

Educational Institutions | Lack of school-based prevention programs. | Rising tramadol abuse among students (37% in Lagos universities). | Oshodi et al. (2022) |

International Partners | Inconsistent funding for harm reduction (e.g., naloxone shortages). | Peer-led programs cover only 5% of high-risk populations. | YouthRISE Nigeria (2022) |

Private Sector (Pharmacies) | Illegal dispensing of codeine (70% in Lagos). | Opioid misuse epidemic; $3.5B annual economic losses. | ICIR (2023); NBS (2022) |

Table 7: Severity of Inactions

Stakeholder | Severity (1–5) | Rationale |

Federal Government | 5 | Systemic underfunding and policy delays cripple national response. |

Law Enforcement | 5 | Corruption enables drug trafficking; 80% cases unprosecuted. |

Healthcare Institutions | 4 | Critical Gaps in addiction services, especially rural areas. |

Private Sector (Pharmacies) | 4 | Illegal codeine sales fuel opioid crisis. |

Communities/NGOs | 3 | Stigma limits harm reduction outreach. |

Families | 3 | Cultural denial delays treatment-seeking. |

Nigeria’s struggle with drug abuse and trafficking is rooted in the systemic collapse of collective responsibility across all sectors. This narrative is defined by the critical intersection of multiple failures: The government exhibits structural neglect through bureaucratic inertia. The National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) is crippled by underfunding, leaving only 15% of planned rehab centers operational (7). This neglect is compounded by the NDLEA’s low prosecution rate (20%) and profound internal corruption, where 60% of drug seizures at Lagos ports involve bribes (8, 12). This collusion enables highly potent substances like methamphetamine and fentanyl to flood the market, cementing Nigeria’s role as a major trafficking hub (2).

The healthcare system reflects deep urban-rural inequity, with rural areas severely underserviced (1 addiction specialist per 500,000 people) (11). Overcrowded psychiatric wards absorb the strain (30% bed occupancy by drug-related cases), but care quality is compromised (FMOH, 2022). This deficit is worsened by pervasive cultural stigma, which attributes addiction to spiritual causes, discouraging individuals from seeking help for common comorbidities like untreated depression (58% of users) (7, 14).

The private sector (pharmacies) exploits weak regulation, with illegal codeine sales driving a 40% surge in opioid dependency (12). Simultaneously, educational and religious institutions fail to act as preventative forces; schools lack programs (37% student abuse rate), and faith-based groups prioritize prayer over evidence-based treatment, leading to higher relapse rates (6, 7).

These shortcomings form a devastating self-reinforcing cycle where underfunded services push addicts into overcrowded care, corrupt officials enable drug flow, and cultural stigma bars vulnerable individuals from life-saving treatment. Breaking this cycle demands immediate, integrated reforms focused on accountability, investment, and dismantling cultural and institutional barriers.

GAPS IN EXISTING EVIDENCE AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Table 8: Gaps in Existing Evidence and Recommendations

Thematic Area | Existing Evidence | Gaps Identified | Recommendations for Research/Policy |

1. Prevalence & Patterns | – High rates of tramadol abuse (37%) among university students (6). | – Limited data on regional variations (e.g., North vs. South). | – Conduct nationwide surveys stratified by region (UN, 2015). |

2. Policy Implementation | – NDCMP achieved only 15% operational rehab centers (7). | – Lack of state-level evaluations of NDCMP. | – Mandate state-level audits of NDCMP progress (Federal Govt. of Nigeria, 2021). |

3. Cultural & Socioeconomic | – 58% of drug users in Abuja attribute addiction to spiritual causes (14). | – No studies on cultural interventions to reduce stigma. | – Pilot culturally adapted anti-stigma campaigns (7). |

4. Healthcare Access | – Rural areas: 1 addiction specialist per 500,000 people (11). | – No cost-effectiveness analysis of rehab models. | – Train community health workers in addiction care (11). |

5. Law Enforcement & Corruption | – 60% of drug seizures at Lagos ports involve bribes (12). | – No studies on technology-driven anti-corruption tools. | – Implement biometric tracking for drug seizures (12). |

6. Mental Health & Comorbidities | – 58% of drug users in Abuja have untreated depression (14). | – No trauma-informed care models for comorbid PTSD. | – Integrate mental health screening into rehab intake (14). |

7. Community Interventions | – Peer-led programs reduce overdoses by 25% in Benue (YouthRISE, 2022). | – No scalability analysis of successful pilots. | – Scale peer-led programs nationally (YouthRISE, 2022). |

8. Methodological Gaps | – Mixed-methods studies rare (6). | – No standardized criteria for evaluating qualitative studies (CASP, 2018). | – Train researchers in MMAT and PRISMA (21). |

The existing evidence base on Nigeria’s drug crisis is highly fragmented and skewed, hindering effective policy formation. Major limitations include a severe paucity of data on substance abuse patterns in conflict-affected and rural geopolitical zones and a lack of longitudinal studies to track evolving trends (5). This obscures regional differences, such as the potential underreporting of female drug use due to cultural conservatism in the North (7).

Critically, there is a fundamental failure in policy evaluation. No studies have assessed state-level compliance with the National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP), despite clear evidence that poor enforcement allows illegal sales (e.g., codeine in Lagos) and limits the operationalization of rehab centers (7, 12). This institutional failure is amplified by systemic corruption, which facilitates 60% of drug seizures being compromised at entry ports (12).

Future efforts must be targeted and evidence-driven: Mandate a nationwide, regionally stratified survey using WHO guidelines, with oversampling in underrepresented areas, and require researchers to use standardized appraisal tools (MMAT, AXIS) to improve data quality and comparability (21, 23). Next is to Implement state-level NDCMP audits and deploy technology, such as biometric tracking of drug seizures and independent oversight bodies, to dismantle institutional corruption (12). There is need to address the dire rural healthcare shortages (1 specialist per 500,000 people) through task-shifting to community health workers and telepsychiatry pilots (1, 11). Mandate mental health screening in all rehab programs to treat high comorbidity rates (e.g., 58% depression) and fund trauma-informed care models (14). Finally, Integrate cultural mediators into anti-stigma campaigns and align rehabilitation programs with SDG 8 (Decent Work) by incorporating vocational training to address poverty-driven trafficking (10, 19). Only through rigorous evidence, multi-sectoral collaboration, and transparent governance can Nigeria effectively dismantle the nexus of inaction perpetuating this crisis.

ECONOMIC AND HEALTH IMPACTS OF DRUG ABUSE IN NIGERIA

Table 9: Economic and Health Impacts of Drug Abuse in Nigeria

|

Nigeria’s drug abuse crisis generates a catastrophic $3.5 billion annual economic loss (10), rooted in a multisectoral failure. This loss stems primarily from productivity declines—with employees exhibiting 25% higher absenteeism (22)—and immense healthcare costs, estimated at $1.2 billion per year for drug-related emergencies (11, 22). This burden is compounded by pervasive corruption, where collusion between cartels and port officials deters foreign investment (12). Crucially, this economic impact is not fully quantified due to a lack of data on the informal economy and losses in key sectors like agriculture (2, 10).

The crisis is also a silent mental health epidemic. Studies show high rates of depression (58%) and psychosis (22%) among drug users, with youth facing a threefold higher suicide risk (6, 14). However, only 10% access treatment due to debilitating stigma (7). This severe mental health burden strains the healthcare system, with 30% of psychiatric beds occupied by drug-related cases, diverting resources from critical care (15). Rural addiction treatment is nearly nonexistent, with only 15% of planned rehab centers operational (7). Private pharmacies exploit this gap, with illegal codeine sales driving a 40% rise in opioid dependency (12).

Furthermore, the intergenerational impacts are dire: parental addiction is directly linked to child labor, reducing annual GDP growth by 1.2% (10, 16). The criminal justice system is simultaneously overwhelmed, with prisons housing 60% drug-dependent inmates, yet the prosecutorial budget resolves only 20% of cases (4, 8).

Addressing this requires a dual-focused approach guided by evidence:

The National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) must align with SDG 8 (employment) to promote corporate responsibility for employee well-being (19). Future research must prioritize quantifying sector-specific losses, particularly in the informal economy (10). Integrating mental health screening into the NDCMP (7) and subsidizing harm reduction strategies (like methadone programs and naloxone) will alleviate the strain on urban centers (15). Policymakers must also conduct cost-benefit analyses comparing rehab to incarceration to inform legislative reforms, potentially including the decriminalization of minor offenses to decongest the criminal justice system (4, 12).

GLOBALIZATION, DIGITAL PLATFORMS, AND DRUG TRAFFICKING IN NIGERIA

Table 10: Globalization, Digital Platforms, and Drug Trafficking in Nigeria

Thematic Area | Existing Evidence | Gaps Identified | Recommendations |

1. Porous Borders & Trafficking | – Nigeria accounts for 87% of pharmaceutical opioid seizures in West Africa due to weak border controls (2). | – No real-time tracking of smuggling routes. | – Deploy AI-powered surveillance systems at borders (2). |

2. Digital Platforms & Drug Access | – 40% of Nigerian youth report purchasing drugs via social media (6). | – No studies on algorithms detecting drug sales online. | – Partner with tech firms to flag drug-related content (6). |

3. Globalization’s Economic Drivers | – Poverty and unemployment (33%) push youth into drug trafficking (10). | – No data on cryptocurrency transactions linked to Nigerian cartels. | – Regulate cryptocurrency exchanges (2). |

4. Cultural Globalization | – Western media glamorizes drug use; 25% of Lagos youth cite hip-hop culture as influencing substance abuse (9). | – No studies on localized media counter-narratives. | – Fund Nigerian filmmakers to create anti-drug content (7). |

Globalization and digitalization have profoundly amplified Nigeria’s drug crisis, transforming the nation into a critical transit hub and enabling new illicit marketplaces.

Nigeria’s porous borders, particularly the Lagos and Port Harcourt ports, facilitate the movement of 87% of pharmaceutical opioids seized in West Africa (3). Cartels exploit weak surveillance, with investigations revealing that 60% of drug seizures at Lagos ports involve collusion and bribes with customs agents (12). Despite this central role in global supply chains, there is a lack of research mapping real-time trafficking routes and economic values, severely limiting enforcement effectiveness (3, 12).

Simultaneously, digital platforms have revolutionized domestic drug access. 40% of youth in Lagos procure substances like tramadol and codeine via social media platforms (Instagram, WhatsApp), utilizing coded language, with vendors offering doorstep delivery (6, 22). The anonymity of encrypted platforms and the lack of advanced cyber-forensic tools for the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) complicate interception (8). This digital globalization intersects with economic inequity; high unemployment (33%) drives vulnerable youth into roles as “drug mules,” while cartels use cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin for untraceable money laundering (2, 3, 10). Culturally, Western media’s glorification of substance use conflicts with traditional community stigma, creating identity confusion among youth (7, 9).

To counter this dual threat, Nigeria must prioritize a technology- and development-focused response by implementing blockchain-based tracking for shipping containers to secure ports (2) and collaborate with tech companies to deploy AI detectors for drug-related keywords on social media (6). The NDLEA should establish an interagency task force with INTERPOL (3). The National Drug Control Master Plan must align with SDG 8 (employment) to create legal jobs for at-risk youth and address the root causes of recruitment into trafficking (19). There is need to integrate digital safety and anti-drug messaging into school curricula and partner with influential local figures (like Afrobeats artists) to reshape youth narratives (YouthRISE, 2022).

Without urgently leveraging technology to secure borders and dismantle the digital marketplace, Nigeria risks becoming a perpetual, digitally-enabled node in the global drug trade, with dire consequences for its public health and security.

GENDER-SPECIFIC BARRIERS TO DRUG TREATMENT IN NIGERIA

Table 11: Gender-Specific Barriers to Drug Treatment in Nigeria

Thematic Area | Existing Evidence | Gaps Identified | Recommendations |

1. Stigma & Cultural Norms | – 70% of women avoid treatment due to stigma, fearing ostracization (7). | – No studies on stigma reduction interventions for women. | – Train female community leaders as stigma mediators (7). |

2. Childcare & Maternal Needs | – <10% of rehab centers offer childcare, forcing mothers to abandon treatment (16). | – No policies integrating childcare into rehab programs. | – Mandate childcare services in all rehab centers (16). |

3. Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities | – Poverty drives 40% of women into drug trafficking (10). | – No vocational programs targeting women post-rehab. | – Integrate skills training (e.g., tailoring) into rehab programs (YouthRISE, 2022). |

4. Mental Health Disparities | – Women with addiction report 2x higher depression rates than men (14). | – No trauma-informed care models for women. | – Train clinicians in trauma-informed care (1). |

5. Policy & Institutional Gaps | – National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) lacks gender-specific strategies (Federal Govt. of Nigeria, 2021). | – No gender-disaggregated data in NDLEA reports. | – Revise NDCMP to include gender benchmarks (Federal Govt. of Nigeria, 2021). |

Gender-specific barriers critically limit Nigerian women’s access to addiction treatment, trapping them in cycles of substance abuse. The foundation of this problem is deeply rooted in cultural stigma and patriarchal norms, where 70% of women avoid seeking help due to fears of being labeled “wayward” or “unfit mothers” (7). This social judgment is less prevalent for men, whose substance use is often culturally normalized as stress relief (6).

This social stigma is amplified by systemic policy and infrastructural neglect: The absence of childcare facilities in rehabilitation centers (less than 10% in Lagos provide it) forces mothers to abandon recovery, contributing to a high relapse rate among mothers (11, 16). Furthermore, specialized care for pregnant, drug-dependent women is virtually non-existent (15). Women with addiction suffer twice the rate of depression compared to men, often linked to unresolved trauma from gender-based violence (GBV) (14). Yet, existing programs focus solely on abstinence, with 60% of women reporting sexual abuse in rehab receiving no necessary trauma counseling (14). Poverty and gender inequality intersect, pushing 40% of women in states like Edo into drug trafficking, often under coercion (10). Female sex workers in Lagos report using heroin to cope with violence, resulting in significantly higher overdose rates (2).

The National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) (2021–2025) exacerbates the issue by lacking gender-specific targets, and the male-dominated National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) often mishandles female cases (8, 17).

Addressing these disparities requires urgent, gender-sensitive reforms: Pilot mother-child rehabilitation units in urban centers and train female counselors in trauma-focused therapies like Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (14, 15). Partner with female religious leaders to reframe addiction as a health issue (7). Revise the NDCMP to adopt gender benchmarks and align rehab programs with SDG 5 (Gender Equality) by integrating vocational training and microloans for women (19). Research must prioritize the undocumented challenges of rural women and the mental health impacts of GBV to inform truly equitable interventions.

META-ANALYSIS OF DRUG ABUSE PREVALENCE ESTIMATES IN NIGERIA (URBAN VS. RURAL)

Table 12: Meta-Analysis of Drug Abuse Prevalence Estimates in Nigeria (Urban vs. Rural)

|

The meta-analysis reveals a significant urban-rural divide in drug abuse prevalence, with urban areas recording 18.2% compared to 12.4% in rural regions. This disparity is driven by contrasting factors: urban prevalence is fueled by high pharmaceutical opioid accessibility and strong peer networks, evidenced by studies showing 37% tramadol abuse among Lagos students and 70% of codeine being bought illegally from Abuja pharmacies (6, 12). Conversely, rural prevalence is closely tied to structural neglect, including high unemployment (33%) pushing farmers into illicit cannabis cultivation as a survival strategy, alongside critical scarcity of addiction specialists (only 1 per 500,000 people) (10, 11). This situation is exacerbated by a severe geographical bias in the literature, as 80% of studies focus on cities, leading to policy responses skewed toward urban centers (5).

The high heterogeneity observed in the analysis (I2=78%, p<0.01) reflects significant methodological inconsistencies across the included studies. Reliability is uneven because only 20% of studies applied standardized quality appraisal tools like AXIS (23), and many neglect reporting guidelines such as PRISMA (20). This methodological variability limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions and undermines data comparability.

To address these challenges, we recommend a dual approach: The Federal Ministry of Health should mandate regionally stratified surveys using standardized WHO criteria to ensure consistent urban/rural definitions. Furthermore, journals should require quality appraisal tools like MMAT (21) to standardize the reporting and reliability of future research. The National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) must be recalibrated to address geographic inequities, integrating rural economic empowerment programs aligned with UN Sustainable Development Goal 8 (19). Furthermore, funding mechanisms should redirect resources, for instance, by deploying mobile clinics in partnership with NGOs like YouthRISE and utilizing technology (e.g., drone surveillance) to address the neglected rural trafficking routes (2). Without bridging this urban-rural research and policy gap, the complexity of Nigeria’s drug crisis will remain poorly understood, leading to inadequate and inequitable interventions.

DISCUSSION

The systematic findings reveal that Nigeria’s drug abuse crisis is an escalating public health catastrophe fueled by a complex interplay of socioeconomic disparity, systemic governance failure, and regionalized drug market dynamics. The national prevalence rate of 14.4% masks critical nuances: regional differences, such as the Northwest’s reliance on cannabis contrasting with the Southeast’s synthetic methamphetamine epidemic, necessitate tailored, localized interventions (5, 8). Furthermore, the crisis is generational, underscored by the alarming 37% tramadol/codeine abuse rate among Lagos university students, highlighting an intersection of academic pressure and easy access to prescription drugs within a failing economy (6).

Poverty (63% multidimensionally poor) and youth unemployment (33%) serve as primary drivers, pushing individuals towards substance use as a coping mechanism or participation in the drug trade (9, 10). This socioeconomic fragility is exploited by deep-seated governance gaps. The illegal dispensing of opioids in pharmacies, where 70% of codeine in Lagos is sold unlawfully, reflects weak regulatory oversight that prioritizes profit over public health (12). This neglect is compounded by corruption within law enforcement, with reports indicating 60% of drug seizures at Lagos ports involve bribes, directly reinforcing Nigeria’s role as a major trafficking hub (12). Culturally, the persistent belief that addiction is a spiritual failing rather than a medical condition perpetuates stigma, delaying treatment and contributing to the cycle of dependency (7).

The public health consequences are dire. Drug-related admissions account for 30% of psychiatric bed occupancy nationwide, yet only 10% of tertiary hospitals offer specialized addiction services (15). The widespread mental health comorbidities, including high rates of depression (58%) and psychosis (22%) among users, underscore the urgent need for integrated mental health care (14). Economically, the crisis exacts a severe toll, estimated at a $3.5 billion annual loss due to decreased productivity and healthcare expenditure, which in turn stifles national economic growth (10).

Collective actions, led by the National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP), represent a crucial attempt at coordination but remain profoundly hampered by policy execution deficits. By 2023, only 15% of planned rehabilitation centers were operational, a shortfall that forces thousands of users into overcrowded psychiatric wards, compromising care quality (17). However, targeted efforts have demonstrated clear success. Community-based interventions, such as the peer-led naloxone distribution program in Benue State, successfully reduced opioid overdose deaths by 25% (18). Furthermore, integrating vocational training with faith-based counseling has been shown to improve treatment adherence by 40% while addressing socioeconomic drivers by reducing drug-related crime by up to 30% in some rural areas (13).

These successes highlight the potential of localized, community-driven, and holistic interventions. Yet, their impact is severely limited by systemic inactions. The National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) prosecutes only 20% of cases due to under-resourcing, allowing cartel impunity (8). The overwhelming demand for treatment outstrips supply, with only 3,000 rehab beds available for 14 million users, leaving rural areas critically underserved and often reliant on spiritual solutions that delay necessary medical care (15). The failure of educational institutions and the private sector (unregulated pharmacies) to act as frontline defenders further exacerbates the problem, especially among youth (6, 12). The consequences of these inactions—from the overwhelming burden on the criminal justice system to the high rate of untreated mental illness—create a self-reinforcing cycle of harm that cannot be addressed in isolation.

The evidence base guiding Nigeria’s response is fragmented. Current research is heavily skewed toward urban centers and specific demographics, resulting in a critical lack of data on rural areas, conflict zones, and marginalized groups like women and children of drug users (9, 16). Longitudinal studies are virtually absent, hindering the ability to track the rising trend of synthetic drugs and measure the long-term effectiveness of interventions.

To bridge these gaps and dismantle the cycle of addiction, comprehensive, accountable action is required: Mandate immediate, fully funded implementation of the NDCMP, especially in infrastructure development. Establish independent oversight bodies for law enforcement (NDLEA) and use technology (e.g., biometric tracking) to combat corruption at ports and enhance the low prosecution rate (8, 12). Integrate addiction services into primary healthcare nationwide, subsidizing medications like naloxone and methadone in rural areas. Implement trauma-informed care protocols for dual diagnosis (addiction and mental illness) and invest in tele-psychiatry to bridge the urban-rural specialist divide (14, 15). Scale up successful community-led models that combine evidence-based treatment with vocational training and socioeconomic reintegration support to address the root causes of poverty and unemployment (13). Conduct a national, regionally-stratified longitudinal survey to track emerging threats and trends. Mandate the use of rigorous reporting guidelines (e.g., PRISMA) and training in advanced methodologies (MMAT, AXIS) to improve the quality and policy relevance of future research (20).

In conclusion, addressing Nigeria’s drug crisis requires a paradigm shift—from viewing addiction as a moral or spiritual failure to recognizing it as a public health issue driven by systemic inequity and governance failures. Without bold investment, accountability, and a holistic, evidence-based approach that tackles both supply reduction and demand reduction, the risk of an irreversible national catastrophe fueled by synthetic drugs and a “lost generation” remains critically high.

LIMITATIONS

This systematic review is subject to several limitations that affect the generalizability and synthesis of its findings. Firstly, the review imposed a language restriction (English only), potentially leading to language bias by excluding relevant research published in indigenous Nigerian or French languages, thereby limiting the capture of region-specific nuances. Secondly, a pronounced geographical bias exists, as the included studies heavily focused on urban centers (Lagos, Abuja) and severely underrepresented rural areas. This limits the generalizability of prevalence estimates and impact analysis to underserved rural populations.

Methodologically, the high heterogeneity in study designs (e.g., cross-sectional vs. mixed-methods) and measurement tools across the included literature challenged data pooling and the derivation of definitive conclusions. Furthermore, the reliance on predominantly cross-sectional data restricted our ability to assess long-term impacts of interventions or the temporal evolution of drug abuse patterns, as longitudinal data is scarce.

The evidence also suffered from the underrepresentation of marginalized groups (women, rural youth, etc), hindering a full understanding of gender-specific barriers and stigma in treatment access. Finally, many studies relied on self-reported data, introducing the risk of social desirability or underreporting bias, which affects the reliability of prevalence estimates. While grey literature was mostly excluded, the limited availability of high-quality, evaluative research on policy implementation and enforcement gaps ultimately constrained the depth of analysis regarding the core themes of collective actions and inactions.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review unequivocally demonstrates that Nigeria’s drug abuse crisis is a systemic, societal challenge, rooted in the intersection of poverty, high youth unemployment, and profound governance failures that have fueled localized drug market dynamics (e.g., synthetic opioids in urban areas). The devastating consequences of inaction—manifested by underfunded treatment infrastructure (only 15% of planned rehab centers operational) and widespread corruption undermining law enforcement—are directly perpetuating the crisis and compounding public health and economic burdens (estimated at $3.5 billion annually).

Despite these barriers, collective actions such as peer-led harm reduction programs and vocational training initiatives have proven effective on a small scale, offering a blueprint for transformation. To turn the tide, Nigeria must adopt a dual-focus strategy: firstly, fully implement the National Drug Control Master Plan (NDCMP) and secure equitable resource allocation to bridge the urban-rural divide. Secondly, Drastically, expand addiction treatment and integrated mental health services, especially in underserved regions, while aggressively confronting the cultural stigma that prevents individuals from seeking necessary medical care.

The systemic nature of the crisis demands accountable, evidence-based, and compassionate multi-sectoral action to secure a future free from the grip of substance abuse for all Nigerians

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of all organizations and researchers whose published data and reports formed the empirical foundation of this review. Special appreciation is extended to the Nigeria Population Commission (NPC) for access to essential demographic datasets and to the numerous peer-reviewed studies and institutional reports cited throughout the manuscript, including those from the Federal Ministry of Health, the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and the World Health Organization (WHO). Their collective efforts enabled a robust, evidence-based synthesis of the public health impact of drug abuse in Nigeria.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M.O conceived and designed the study, led the systematic review process, and coordinated manuscript development. TE conducted literature search, data synthesis, and policy analysis, GCT provided oversight on methodological rigor, quality assurance and interpretation of findings. EBA performed data validation, verification of datasets, and consistency checks across sources. PDO reviewed pharmacological implications and contributed to discussion and referencing, KID edited the manuscript, reviewed formatting, and ensured citation accuracy, UGE advised on pharmacovigilance and national policy alignment. TRW managed visual data presentation and final manuscript proofreading. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. No author has any financial, institutional, or personal relationship that could inappropriately influence the reporting or interpretation of the study

FUNDING

This study was conducted without external funding. No financial support was received from governmental, commercial, or not-for-ptofit organizations. All costs related to the research, data analysis, and publication preparation were borne by the authors as part of their academic responsibilities

References

- Global status report on substance abuse. Geneva: WHO; 2021.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Drug use in Nigeria: 2018 survey. Vienna: UNODC; 2018.

- World Drug Report 2021. Vienna: UNODC; 2021.

- Eze C, Okeke T, Okafor C. Drug trafficking and governance in West Africa. International Journal of Drug Policy; 2021;89:103–12.

- Abdulmalik J, Olayinka O, Oshodi Y. Substance abuse among youths in Nigeria: A review of the literature. African Journal of Psychiatry; 2019;22(3):123–30.

- Oshodi Y, Abdulmalik J, Olayinka O. Tramadol abuse among university students in Lagos: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Addiction Research; 2022;15(4):45–56.

- Adelekan ML, Abiodun OA, Obayan AO. Evaluation of the National Drug Control Master Plan in Nigeria: Achievements and challenges. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment; 2021;45(3):123–34.

- Annual drug seizure report. Abuja: NDLEA; 2023.

- Oshodi YO, Aina OF, Onajole AT. Substance use among secondary school students in Lagos, Nigeria: Prevalence and associated factors. Journal of Addiction; 2020;15(3):234–45.

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Nigeria poverty and unemployment report. Abuja: NBS; 2022.

- Oluwaseun AT, Adeyemi OS, Oluwatoyin AM. Access to drug abuse treatment and rehabilitation services in Nigeria: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research; 2023;23(1):45–56.

- Corruption in Nigerian ports. Investigative report. 2023.

- Okeke SR, Onyebueke GC, Nwankwo EA. Community-based interventions for drug abuse prevention in Nigeria: A systematic review. African Journal of Public Health; 2022;14(2):89–101.

- Okafor C, Eze C, Okeke T. Mental health comorbidities among drug users in Abuja. Nigerian Journal of Psychiatry; 2023;15(1):22–30.

- Federal Ministry of Health. National health statistics report. Abuja: FMOH; 2022.

- Child labor and parental substance abuse in Edo State. Abuja: UNICEF Nigeria; 2022.

- Federal Government of Nigeria. National Drug Control Master Plan (2021–2025). Abuja: FGON; 2021.

- YouthRISE Nigeria

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals. New York: UN.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71.

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., … & Rousseau, M. C. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018. Retrieved from http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/

- Olanrewaju, J. A. (2022). An assessment of drug and substance abuse prevalence: A cross-sectional study among undergraduates in selected southwestern universities in Nigeria. Journal of International Medical Research, 50(10), Article 03000605221130039.

- .Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), e011458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458